By Donald Wittkowski

As the fighting in World War I raged thousands of miles away in Europe, New Jersey had its own macabre front-row seat of sorts to the death and carnage.

German submarines prowled the waters just off the New Jersey coast searching for Allied ships to sink. When the U-boats attacked their prey, the fiery explosions were visible at night from the boardwalks in Asbury Park and other towns lining the Jersey Shore.

“They would watch the explosions from what would go on at night,” Jeffrey Pierson, a retired Army brigadier general, said of the seashore residents during the war.

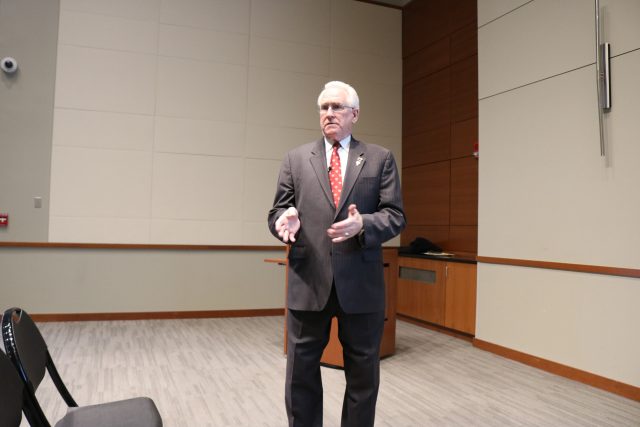

Pierson, a Cape May County freeholder who had a 42-year career in the Army and New Jersey National Guard before entering politics, recounted New Jersey’s involvement in World War I during a presentation Wednesday at Stockton University.

His remarks came just three days after the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day, which finally brought the bloody “War to End All Wars” to a close on Nov. 11, 1918.

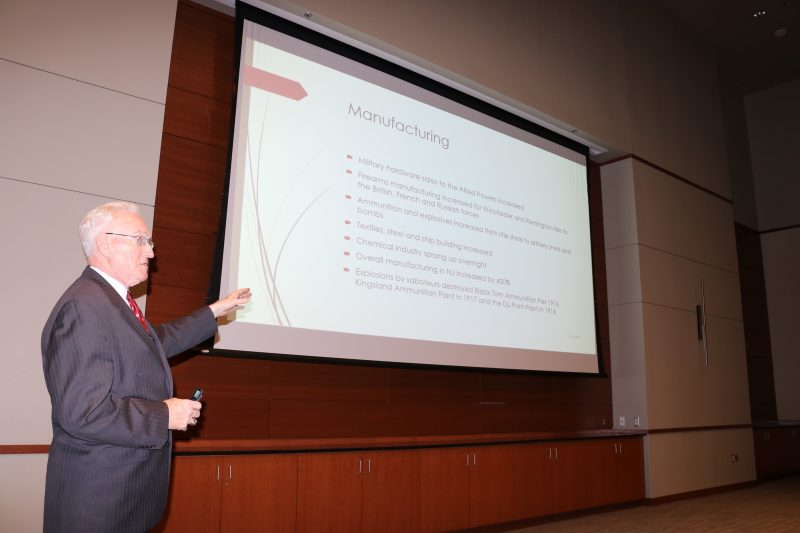

New Jersey’s contributions – and huge sacrifices – during the war have faded over the past 100 years. Pierson, though, rekindled the memories by pointing out that the state served as a major manufacturing center for the war effort and the primary port of embarkation for American soldiers heading overseas.

Moreover, about 150,000 troops from New Jersey served in the war, including 10,000 from the New Jersey National Guard. Altogether, 3,836 New Jersey soldiers were killed in combat or died from disease or accidents during the war, Pierson noted.

When the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917, the New Jersey National Guard didn’t have any African-American soldiers. However, 50 African-American men from Newark joined New York’s 369th Infantry Regiment, a highly distinguished unit during the war that became known as the “Harlem Hell Fighters,” Pierson said.

Hoboken, N.J., became the primary port of departure for soldiers leaving for Europe. It also served as the main port for troops returning home after the war ended. In all, about 4 million American troops passed through the Port of Hoboken, Pierson said.

“Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken” became a slogan for troops hoping for a safe return home. The war brought major changes to life in Hoboken, and the city would not be the same after the war, according to the Hoboken Historical Museum website.

The horrors of war also hit close to home at the Jersey Shore. German submarines lurked just off the coast looking for Allied shipping. In those days, U-boats often would sink ships using their deck guns, creating flashes of fire visible at night to residents of the seashore towns, Pierson explained.

“You could watch the explosions and the ships right off the shore,” he said.

Pierson recalled that the German submarine U-151 sank six ships off the New Jersey coast on June 2, 1918, an infamous day that was dubbed “Black Sunday.” One of the ships was the 380-foot passenger liner SS Carolina, which went down about 65 miles east of Atlantic City.

After the war ended, the New Jersey National Guard was disbanded and then went through a reorganization. The pay was low for National Guard members at that time, so New Jersey used its seashore location as an incentive to attract new recruits.

Pierson said the National Guard told recruits that they would enjoy the luxury of going “boating, fishing and swimming” when they were off-duty.

The 76-year-old Pierson, who joined the National Guard in 1961 and served in the military until his retirement in 2003, joked that the New Jersey National Guard should add another seashore attraction in its efforts to recruit new members these days.

“Now, I would say boating, swimming, fishing and great restaurants,” he quipped, drawing laughs from the Stockton audience.

One audience member, Jeff Schenker, of Toms River, is the vice president of the Ocean County Historical Society. Schenker was on hand for Pierson’s remarks as part of research he is doing for a new book about New Jersey’s involvement in World War I. The book, not yet titled, is expected to be a two-year project.

Schenker said he was able to learn some historical information from Pierson’s presentation, including the extent of New Jersey’s wartime manufacturing and Hoboken’s role as the main port of departure for American troops.

Afterward, Schenker, who has a doctorate in history from New Jersey’s Drew University, spoke to Pierson for several minutes. He ended their conversation by thanking Pierson for his military service.

“I think he’s an extremely impressive person,” Schenker said of Pierson in an interview. “His credentials are unbelievable.”