By Donald Wittkowski

Terms such as “lockdown,” “active shooter,” and “cyber threat” have become part of the modern vernacular in U.S. schools.

With one national study showing that nearly 1 million students bring a gun to school each year, school officials across the country are scrambling to develop security measures to prevent more mass shootings like those at Columbine High School in Colorado and Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut.

With those school tragedies and others still fresh in their minds, Cape May County school officials and security experts convened a security summit Tuesday night at Ocean City High School to discuss ways to protect students and school employees from violence.

“Obviously, school security is our first and primary concern in every school district,” said Jacqueline A. McAlister, president of the Cape May County School Boards Association, the group that held the summit, the first of its kind in the county.

McAlister, who also serves as vice president of the Ocean City Board of Education, said the summit gave school officials an extraordinary opportunity to share ideas on ways to improve security.

“The more we open our door to conversation, the better,” she said.

For three hours at the summit, school representatives, security specialists and law enforcement officials focused on the growing threat of mass shootings at schools nationwide and what steps might be taken to prevent such a tragedy from happening in the Cape May County schools.

One speaker, Garry Hodge, a security expert and special investigator for the New Jersey Department of Education, warned the audience it would be a grave mistake to become complacent and think that a shooting could not occur in their schools.

“Nobody can guarantee that an incident will not happen in their school,” Hodge said.

Hodge equated school security plans to a life insurance policy – schools may not always need them, but they are there just in case they do.

Jim Corbley, Hodge’s colleague and a government representative at the Department of Education, said New Jersey “is at the forefront nationwide” of school security. Still, he stressed that school officials should never let down their guard.

“You don’t prepare for the best. You prepare for the worst. And you hope for the best,” Corbley said.

Ben Castillo, director of the New Jersey Department of Education’s Office of School Preparedness and Emergency Planning, explained that the state requires schools to develop safety and security plans and to conduct emergency drills on a regular basis.

Castillo’s office helps New Jersey’s schools to develop and evaluate their safety and security plans, which must contain 91 minimum requirements.

“It’s got to address all hazards,” Castillo said.

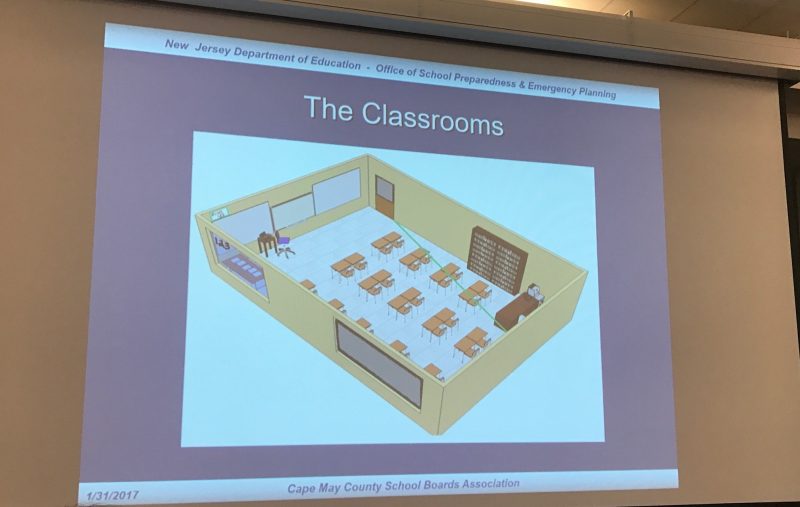

Another important function of Castillo’s office is to conduct surprise visits to observe schools when they run practice drills for the threat of an active shooter and go through simulated lockdowns.

Castillo said there are no signs yet that students are starting to develop “drill fatigue,” but he did express concerns about the possibility of them not taking emergency exercises seriously.

“One of the problems we see in school, there is some complacency: ‘Oh, it’s a drill,’” he said.

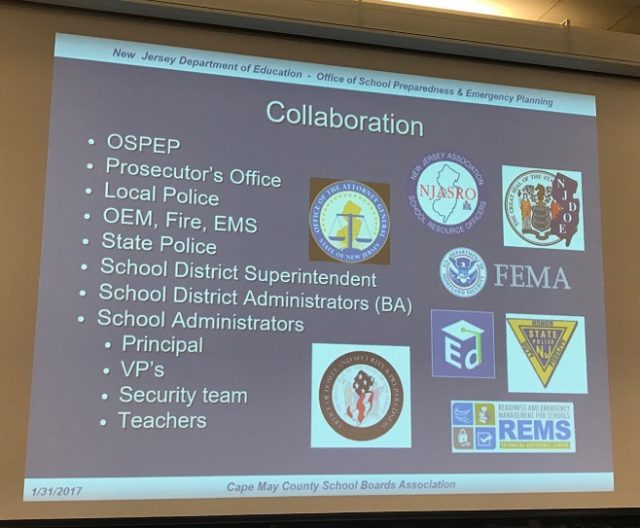

One of the recurring themes at the security summit was the need for school officials to collaborate with law enforcement and other experts to develop extra layers of defense to protect schools.

Cape May County Freeholder E. Marie Hayes, who was one of the summit speakers, said the county is fully committed to helping with school safety.

“We will be there for you,” she told the audience. “I believe we have already proved that.”

Hayes, now retired from a 29-year career in law enforcement, specialized in child abuse cases when she served as captain of detectives in the Cape May County Prosecutor’s Office.

“We have to protect the vulnerable – our children,” she said of school safety.

Capt. Jay Prettyman, of the Ocean City Police Department, noted that the department has worked closely with the local schools on their security plans for about 20 years. The Columbine High School massacre in 1999 forever changed things in school security, he pointed out.

“We remember Columbine well,” Prettyman said.

Geoff Haines, principal of the Ocean City Intermediate School, called Columbine “the one that really changed the game.”

Haines described an array of locking doors, surveillance cameras and other security measures that are in place to control access to the intermediate school, so “the bad guy cannot get in.”

For instance, visitors to the intermediate school must ring a buzzer at the front door to gain entrance to the building and then must pass through a secured vestibule before they are allowed into the school office. There, they must sign in and get a visitor’s pass, all under the watchful eye of school staff, Haines said.

Physical barriers are not the only way to improve school safety, Ocean City Superintendent of Schools Kathleen Taylor said. She emphasized the need for mental-health programs in the schools to help at-risk students before they become “fractured’ and commit violent.

In recent years, cyber threats have become increasingly common at schools nationwide. The explosion of social media has added another potentially dangerous element to school security and student safety, said Rich McHale, security director at the Cape May Technical School District. McHale mentioned how two girls recently live-streamed their suicides on social media outlets.